Grateful Dead

- posterpchb

- Sep 10, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Sep 16, 2025

[Text prompted from Ai by Erik]

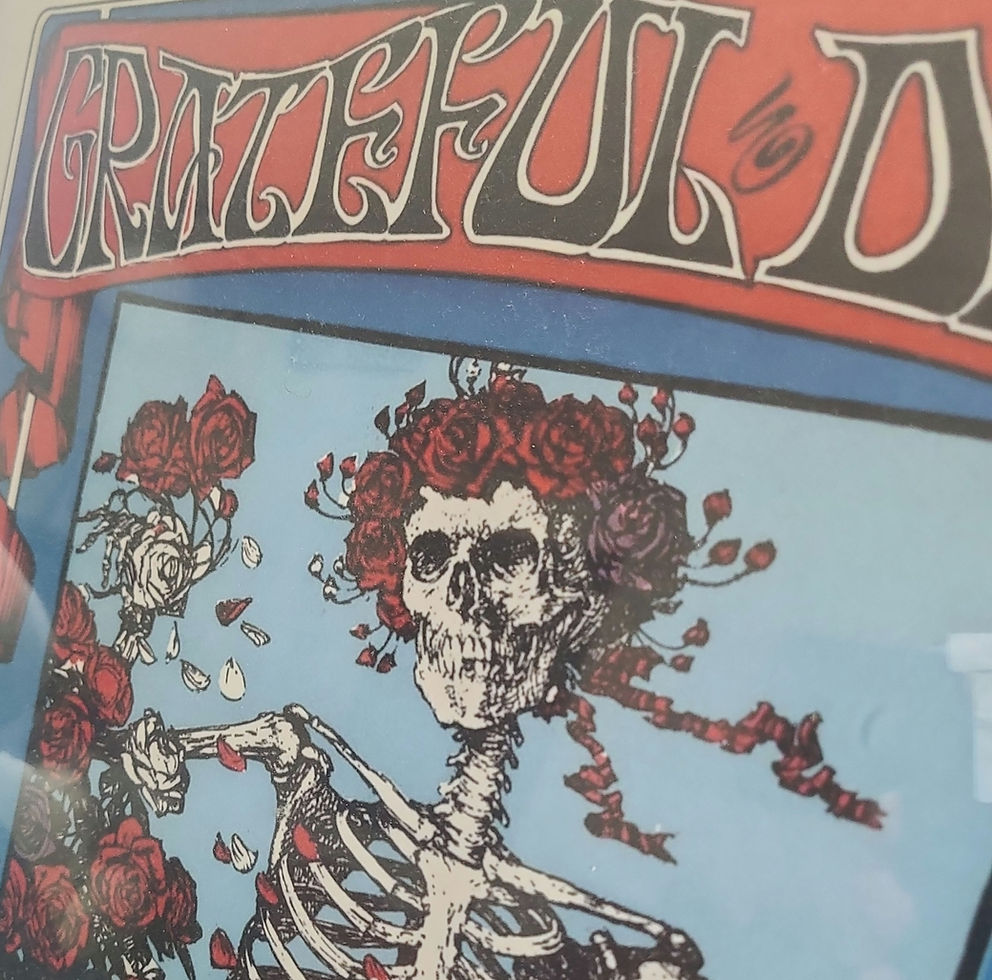

Concert Posters and Visual Culture

The Grateful Dead were closely tied to the psychedelic poster art movement. Promoters needed ways to advertise shows, and artists transformed posters into vibrant works of art.

Key figures included Wes Wilson, who pioneered the flowing, distorted typography; Victor Moscoso, known for his eye-popping color contrasts; Rick Griffin, whose surreal imagery became synonymous with the Dead; and the duo Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse, who blended art nouveau with counterculture symbolism.

These posters were as much a part of the experience as the music itself. They captured the psychedelic spirit visually, turning concert promotion into a collectible art form and leaving a legacy that continues to influence graphic design.

1965–1972

Emerging from San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury in 1965, the Grateful Dead became the quintessential hippie-era band. Their eclectic blend of rock, folk, blues, and improvisation created a unique sound that thrived on stage rather than in the studio. More than a band, they became the hub of a countercultural community later known as the Deadheads.

Musically, the Dead defied convention. Extended jams turned simple songs into exploratory journeys, while lyrics co-written with poet Robert Hunter evoked Americana, mysticism, and freedom. They were less overtly political than some peers, but their communal living, benefit concerts, and anti-commercial ethos reflected the values of the era.

The core lineup included Jerry Garcia (lead guitar, vocals), Bob Weir (rhythm guitar, vocals), Phil Lesh (bass), Bill Kreutzmann (drums), and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (keyboards, harmonica, vocals). Mickey Hart (drums) and Tom Constanten (keyboards) joined at various points. Pigpen’s blues roots and Garcia’s visionary guitar anchored their early sound.

Albums like Anthem of the Sun (1968) and Aoxomoxoa (1969) captured their experimental edge, while Live/Dead (1969) showcased their legendary stage improvisation. In 1970, Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty revealed a more song-oriented side, yielding enduring classics like “Uncle John’s Band” and “Friend of the Devil.”

Their reputation was cemented in concert halls: the Fillmore West and Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, and the Fillmore East in New York. Promoter Bill Graham professionalized their shows at the Fillmores, while Family Dog’s Avalon embodied the free-spirited, communal ethos. These venues declined as the scene shifted to larger arenas, but in their time they defined an era.

Between 1965 and 1972, the Grateful Dead built a legacy not of hit singles, but of freedom, improvisation, and community — the true spirit of the hippie era.

Comments